Introduction

Despite a population of only 5.6 million, Norway is a powerhouse in endurance sports. The country won the most Olympic gold medals at the 2014, 2018 and 2022 Winter Games and Norwegian athletes routinely win top trophies at the Olympic, World and European Championships.

How to explain such a resounding success? Are Norwegian coaches planning, managing and monitoring training in a special way? Do they share of unique periodization principles or ‘secret’ methods that may explain their athletes’ outstanding and consistent performances?

This is the question that a Norwegian research team tried to answer in two very interesting research papers, published in 2024 and 2025.

In the study, researchers asked 12 highly successful Norwegian endurance coaches, who trained more than 370 medal winners across multiple endurance sports, to describe their macro, meso and micro-cycles periodization models, session planning and training intensity management strategies.

This document summarizes their findings.

Method

Participating coaches completed an extensive questionnaire in which they described: 1) how they plan and periodize training at the macro, meso, microcycle and session levels, and; 2) how they manage day-to-day training and the volume/intensity of training sessions and, finally; 3) how they monitor training responses while ensuring quality control.

Researchers then cross-referenced coaches’ answers with training logs of their most successful athletes, and conducted interviews (approx. 180 min) with each coach.

Results

Training periodization model

Coaches surveyed in the study reported using a traditional annual periodization approach similar to the one proposed by Matveyev in the 1950s.

The Matveyev model typically splits the yearly calendar in 4 distinct periods: 1) a general preparation period characterized by high training volume; 2) a specific preparation period with increased intensity and specificity; 3) a competition period characterized by reduced volume, high intensity and high sport specificity and ; 4) a transition period that includes reduced volume or intensity.

While using a traditional periodization model, coaches do it in a very flexible way. For example, they may incorporate blocks of high training volume between competitions as well as recovery weeks, periods dedicated to skill development or altitude training at any time during each of the annual plan periods, whenever these strategies may lead to better performance development.

Management of training volume

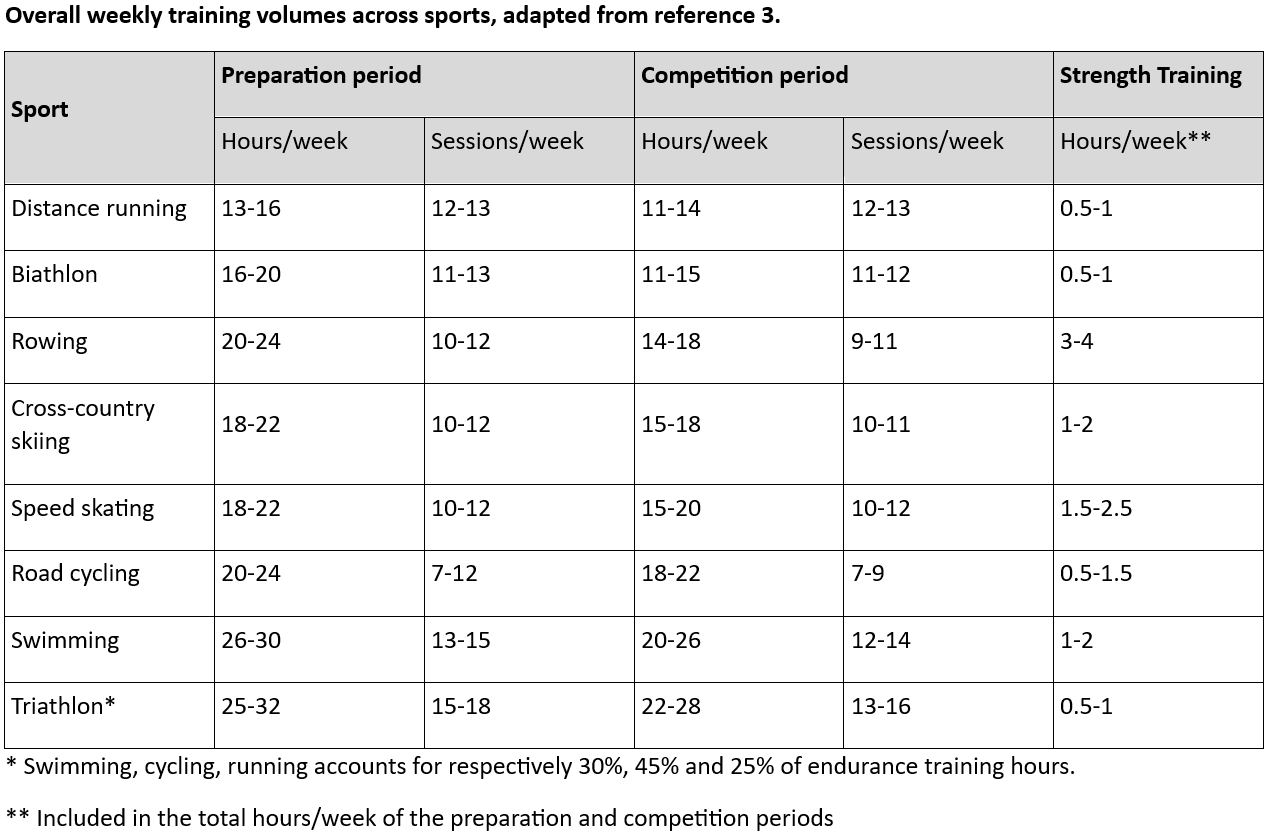

All coaches consider the accumulation of high training volume the cornerstone of their training philosophy. The highest training volumes are reported in triathlon, with 1400hrs/year, while the lowest are in long distance running (600h/year). Differences in training volumes are explained by the differences in mechanical stress caused by training activities.

Biathlon, cross-country skiing, rowing and speed skating

Training volume is kept high and an ‘easy week’ (25-35% reduction of training volume) is scheduled every 3-4 weeks.

Reduction in training volume is usually achieved by removing 1-2 sessions/week and reducing the duration of low intensity sessions.

This reduction in training volume is not applied during the competitive season as load adjustments are guided by the competition schedule.

Distance running, swimming and triathlon

Training volume is relatively even week-to-week. Reduction in training volume occur during travel, altitude camps and competitions.

Road cycling

Training volume is high and fairly constant. As the competitive season spans over 8 months, recovery periods and blocks of high training volumes are often scheduled after stage races.

Management of training intensity

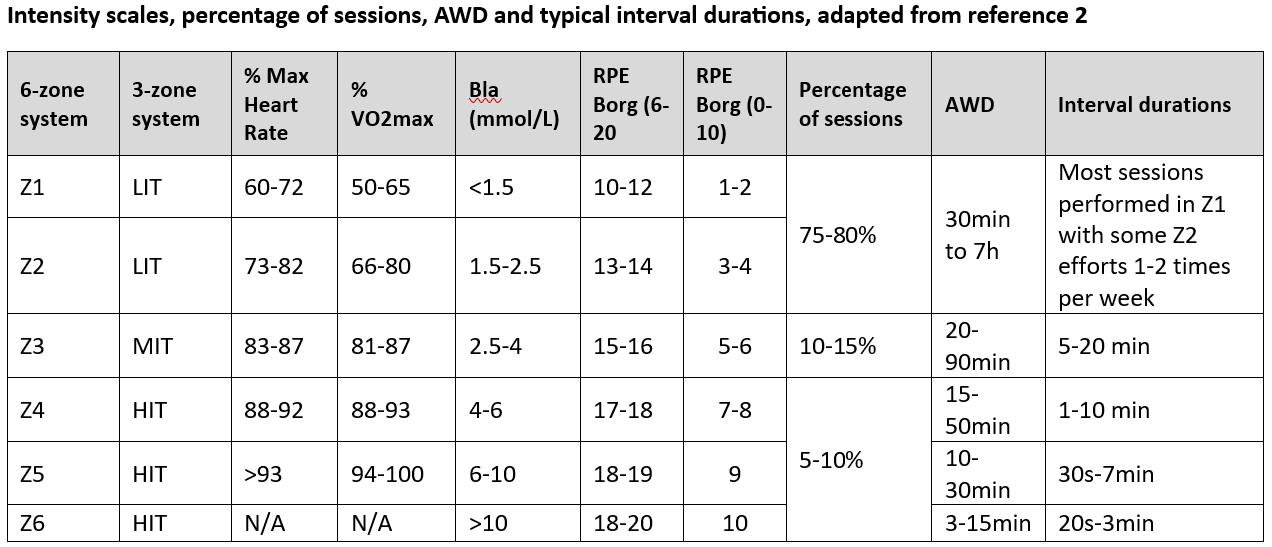

Training intensity was quantified using the six-zone system developed by the Norwegian Elite Sports Centre (Toppidrettssenteret, Olympiatoppen). The corresponding 3-zone system Low Intensity Zones (LIT), Medium Intensity Zones (MIT), High Intensity Zones (HIT) and related VO2, lactate and RPE zones was also provided.

For interval training sessions, an ‘accumulated work duration’ (AWD) index, defined as the sum of all intervals, excluding warmup, cooldown and recovery were also calculated.

The distribution of training intensities over the annual cycle is calculated by adding the total number of sessions performed in each intensity zone.

Across sports, the vast majority of sessions performed during the annual cycle are Z1-Z2 (LIT) sessions, using continuous exercises. Most Z4-6 sessions and many Z3 sessions are performed during competitions.

Tapering

During periods immediately preceding important competitive events, training frequency and intensity remain the same, but the duration of sessions is reduced by up to 50%. Strength training is often eliminated.

Day to day adjustments

Most coaches use a similar day-to-day scheduling model. That includes two sessions per day for most days, and the alternance of hard and easy days, with two or three hard days each week. Low intensity training is performed between hard days.

Adjustments of weekly training volume are usually made by increasing or decreasing the duration of the low-intensity sessions.

Training monitoring

Coaches are using a holistic approach to training monitoring and ensuring training quality control. They are using both objective (lactate measurements, diaries, standardized sessions, technology) and subjective (athlete feedback) data to monitor internal load, adjust external load and adapt schedules according to the athlete’s response.

Summary

Here is a summary of the best practice methods commonly used by the highly successful Norwegian endurance coaches who participated in the study. They:

- Use a traditional periodization model with flexibility and sport-specific variations

- Focus on high training volumes during the preparation period

- Plan a 25-35% reduction of training volume every 3-4 weeks

- Increase training intensity and sport specificity closer to competitions

- Add training blocks of various focus (altitude, recovery, skills, etc.) thorough the year

- Dedicate 85-95 % of total training volume to aerobic endurance training, of which 80-90% performed at low intensity (Z1-Z2)

- Define the quality of training not by the amount of high intensity work, but by how sessions are best planned and executed in order to optimize adaptations and improve overall performance

- Use a small set of session models for each intensity zone and training goal

- Consider MIT and HIT sessions key to performance progression but schedule considerably more LIT and MIT sessions than HIT ones during the annual cycle

- Consider the training day as the main unit of stress

- Alternate hard and easy training days

- Plan two to three hard days per week (usually Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday), inter-spaced with low-intensity days

- Prefer to double the intensity of hard days when required (schedule two interval sessions, one in the morning and one the afternoon) rather than adding an extra hard day in the week

- Mix intensity zones within each session

- Do not often use all-out sessions

- Use passive recovery

- Use lactate measurements to control intensity zones, particularly during MIT and HIT sessions, rather than speed and power measures

- Use their own observations, athlete feedback and objectives markers to monitor training and ensure quality control

Conclusion

This analysis of best practices of some of the world’s most successful endurance coaches, illustrates how a few and relatively simple guiding principles, can be used to best prepare endurance athletes towards world-class performance.

It is also important to note that, in additional to having exceptional endurance coaches, top Norwegian athletes are also benefiting of high-quality support, including an innovative national athlete health monitoring program, described by Clarsen et al1.

The combination of world-class coaching and athlete health care programs ensures that athletes are not only prepared to excel at the highest level whenever required, but also remain healthy, and ready to sustain high training loads safely.

Read the original articles on the publisher site

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-024-02067-4

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s40798-025-00848-3

About the author

Francois Gazzano is a performance coach and athlete monitoring specialist who graduated from the Université de Montreal with a degree in Exercise Science. As a full-time strength and conditioning coach and performance consultant in Europe and North America for more than 15 years, François has helped dozens of youth, elite and professional athletes across a wide range of sports reach their highest performance goals.

Francois is also the founder & CEO of AthleteMonitoring.com (athletemonitoring.com), an evidence-based athlete health and performance management platform used by elite sport organizations in more than 80 countries.

Francois can be reached on LinkedIn or by email: francois@fitstatstechnologies.com.

References

- Clarsen B, Steffen K, Berge HM, et al Methods, challenges and benefits of a health monitoring programme for Norwegian Olympic and Paralympic athletes: the road from London 2012 to Tokyo 2020, British Journal of Sports Medicine 2021;55:1342-1349. https://bjsm.bmj.com/content/55/23/1342.info

- Tønnessen E, Sandbakk Ø, Sandbakk SB, Seiler S, Haugen T. Training Session Models in Endurance Sports: A Norwegian Perspective on Best Practice Recommendations. Sports Med. 2024 Nov;54(11):2935-2953. doi: 10.1007/s40279-024-02067-4. Epub 2024 Jul 16. PMID: 39012575; https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40279-024-02067-4

- Sandbakk, Ø., Tønnessen, E., Sandbakk, S.B. et al. Best-Practice Training Characteristics Within Olympic Endurance Sports as Described by Norwegian World-Class Coaches. Sports Med – Open 11, 45 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-025-00848-3

- Borg G. Psychophysical scaling with applications in physical work and the perception of exertion. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1990;16 Suppl 1:55-8. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1815. PMID: 2345867.